Ever since it appeared in the reporting requirements related to the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), a lot of sustainability teams have been discussing the how and what of the term ‘double materiality’. Companies ask themselves (or us): “What is double materiality? What exactly is the difference with ‘traditional’ materiality processes?”

What is double materiality?

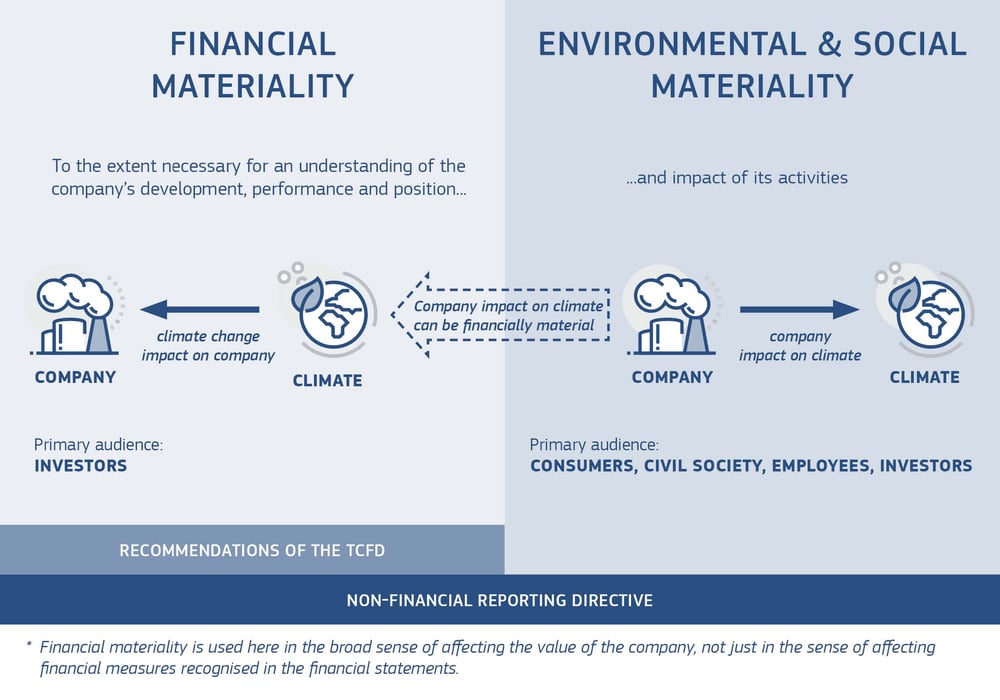

The ESRS standards 1 and 2 coin the term double materiality. It says that companies should evaluate the ESG topics that have a significant financial effect on their current or future position (financial materiality) – but equally, the ESG topics through which they have a significant influence on people and the environment (impact materiality). If you take a look at it from a distance, it doesn’t sound illogical at all. You manage best what can hurt or give you wings financially – or your biggest impacts – or of course both.

(source: EU Commission)

What is double materiality – and how does it differ from how materiality was run in the past?

In discussions with companies, we sometimes get to the point of asking ourselves: where does exactly the difference lie with traditional materiality processes? We think the devil is not at all in the detail. There are some clear shifts.

The double materiality perspectives (financial and impact materiality) are much more pertinent and stringent than traditional materiality perspectives.

Answering the question ‘what is important for the company’ is from a different (say: high-level) magnitude than figuring out which topics can have a significant impact on cash flow, market share, access to finance, or balance sheet risk. Needless to say, the latter will require rigorous analysis and new stakeholders participating in the process. This is what double materiality pushes you to do.

Answering the question "What is important to stakeholders?" is, in turn, totally different than trying to find out where the company’s main (positive or negative) impacts lie – and how they resonate throughout the value chain. External stakeholders can and will help out by articulating their views, but they’re only one part of the puzzle. This part of the process will rigorous data and stakeholder analysis on environmental, social, and governance trends, throughout the value chain.

You sense immediately that evaluating double materiality should go further than the occasional senior mgmt. interviews and internal/external stakeholder surveys – like it was done in the past. It requires (data) analysis, benchmarking – and deep(er) stakeholder engagement than before.

Global technology company Barco does this well, even incorporating a data-driven view on materiality. Read up on their materiality process here. Want to know more about data-driven materiality? Fast forward to this article.

Material topics are pinpointed through the identification of (financial) risks and opportunities, and impacts

Double materiality pushes you to evaluate the materiality of topics by asking 3xWHY. Only then do you arrive at the level of risks, opportunities, and impacts (RIO) that are at the basis of any material topic. This information provides you with the rationale for why certain topics are material for your organisation or value chain.

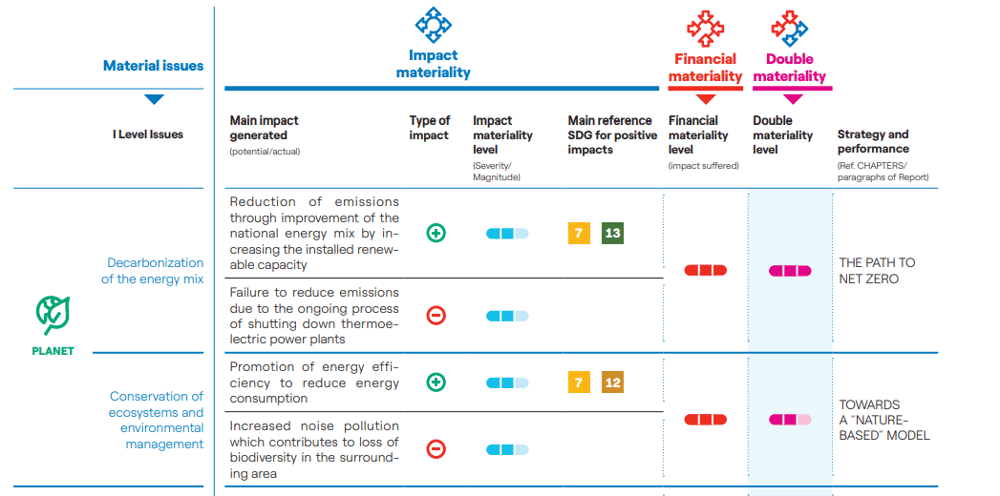

Where traditional materiality saw building a materiality matrix as the holy grail, double materiality leads to a RIO assessment, for example in the form of a table, where material topics are linked to clear (financial) risks and opportunities, or impacts.

Power company Enel already links risks, opportunities, and impacts to material topics fairly well – read all about their double materiality process here. The abstract below shows a double materiality table – with material topics with associated impacts, risks, and opportunities.

The strategic value of double materiality: a case example from the polymer industry

Let’s take a look at a tangible case from the polymer manufacturing industry. Various forces push polymer manufacturers to shift from non-renewable resources towards renewable alternatives, be it recycled, bio-renewable or CO2-sourced polymers. The ESG-topic circular economy, and more specifically, switching to circular carbon is highly material for plastics value chains – and for polymer manufacturers especially. We can find the rationale by rigorously evaluating both the financial and impact materiality of the topic.

-

Impact materiality: the environmental impact of the use of fossil resources is apparent and proven, and mainly contributes to climate change effects due to greenhouse gas emissions both upstream of the value chain and due to poor end-of-life management. Various polymer categories show low collection rates and recycling rates that prove to be challenging to raise.

-

Financial materiality: Regulatory pressure (eg. single-use plastics directive) and end-customer preference shifts (embodied by stringent SBTI targets) push polymer producers to integrate circular carbon raw materials. Transition risks and opportunities are myriad in the circular transition. Polymer producers are challenged to integrate renewable resources while keeping product performance at par (technical risk). Simultaneously, renewable resource value chains still need to be developed and deployed at scale, resulting in market risks because of high-priced circular raw materials. This can, in turn, influence the market share of polymer producers – or the affordability of end-products.

-

Analysing risks, opportunities, and impacts related to the circular transition can push manufacturers into starting up new research development programs, investing in M&A for the promising start of scale-ups, or closing new supplier agreements.

In conclusion, evaluating the materiality of key ESG topics gives organisations a solid insight into key (financial) risks and opportunities. And that’s exactly what we need to get the attention of CXOs, strategy analysts, and boards to make decisions and allocate resources – and to elevate materiality to the place where it belongs: the strategy room.