A significant passage in the book "Scarcity: Why having too little means so much" tells the story of Lieutenant Chapanis. During World War II, Alphonse Chapanis investigated the causes of the many accidents that occurred when landing the B-17 and B-25 bombers in the American Army. After observing the cockpits in these planes, he realised that the lever for retracting the landing gear was very similar to the lever for retracting the flaps, and that the two levers were placed side by side. Accidents were certainly due to errors by the pilots, but these errors were caused by the cockpit. By adding a small rubber wheel on the lever for the landing gear, Chapanis successfully reduced the number of this type of accident.

Alphonse Chapanis proved that a poor cockpit design could cause piloting errors, even among experienced pilots with perfect training. Wouldn’t this also be the case in the business world, where a poorly designed scorecard could lead to erroneous decisions? I am sure it would.

Business leaders should be constantly looking for balance between contradicting goals. Better serving customers, or reducing costs? Buying large quantities at the lowest price, or avoiding overstocking? Investing in automated logistical solutions, or maintaining a flexible workforce? In the complex world of business, everything is interdependent. You can’t act on a single lever. "All things being equal" is a very deceptive phrase. And yet it is what our scorecards, often too single-minded, lead us to believe.

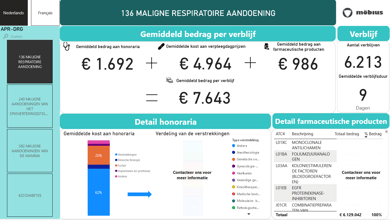

In her book "Metrics that Matter", Lora Cecere explains the importance of balanced indicators and objectives. A balanced scorecard shows combinations of indicators (service rates and stock coverage, overall equipment effectiveness and inventory value, etc.) so that decision-makers can remain aware of the influence of each action on performance as a whole, and avoid being blinded by hoped-for improvements in a single aspect of performance.

But just having balanced indicators is not enough. The indicators must also show a path towards the target. What are the company’s strategic objectives? Are the strategic objectives visible in the indicators being measured? If not, then how can you hope to achieve them?

In “Psychology and the Instrument Panel”, an article published in Scientific American in April 1953, Chapanis showed that the mere complexity of instrument panels in war planes led pilots to make mistakes. One final lesson for those aiming to better steer our businesses: above all, a good scorecard should be easy to interpret. A legible and meaningful visualisation is much less trivial than it may seem.

Improving decisions at all levels of a business can benefit from a well-considered design of the scorecards in use. We have all of the technical tools we need. But do we put in enough effort when selecting and displaying the indicators that influence our decisions?